“We Were Special Long Before Ape Descent”: Interview with Neuroscientist Nikolai Kukushkin

Workplaces / / January 07, 2021

Nikolai Kukushkin is a neuroscientist who works and teaches at New York University. He studies memory, nervous system and evolution. Recently Nikolai's book “Clap with one palm. How inanimate nature gave birth to the human mind ", in which the author shows that we were special at each turn of our evolutionary path, and step by step recreates our history: from inanimate matter to human mind.

We talked with Nikolai about evolution and the brain: we found out how the appearance of speech influenced human development, how memory works and why we remember stupid songs, but forget about a friend's birthday. And they also learned what can be understood about a person by studying mollusks.

Nikolay Kukushkin

Neurobiologist, author of the popular science book “Clap with one palm. How inanimate nature gave birth to the human mind. "

About the work of a neuroscientist and slugs

- What are you studying now?

I study the molecular and cellular mechanisms of long-term memory. This is closer to cell biology than traditional neuroscience, because I usually do not work with whole organisms, but with individual cells and neurons or a pair of cells that are connected between yourself. Naturally, exploring the global mechanisms of memorization that are applicable to humans and other animals.

I am interested in how the signals received by the nerve cells are integrated into a long-term response, such as the formation of long-term memory. Relatively speaking, how does a cell know that something has been repeated several times. Or how she knows that one of the incentives is more important than another.

- Do you remember that moment in your life when you decided to devote yourself to science?

I was born into a scientific family and grew up with the feeling that it was natural and obvious to do science. I am already a third generation scientist. There was no moment when it came down to me that I want to be not astronaut, but a scientist. But it happened that I seriously thought about something else.

For example, after the 9th grade, I entered the lyceum at the First St. Petersburg State Medical University. Then medicine fascinated me and it seemed that this is what I want to do. But who turned me out of medicine or chemistry (all my relatives are chemists, I am the first biologist in my family) is my biology teacher Tatyana Viktorovna Selennova. She is young, stylish and temperamental, we wanted to be like her in some way.

I realized that biology is not necessarily old people in a dusty botanical laboratory looking at something through a microscope. It can be very interesting and exciting. So I went to the biology department and have been doing it ever since.

- Why neuroscience? Why are you so interested in the brain?

What biology means to me has changed a lot over time. When I entered the Biological Faculty, I was not at all interested in animals, plants and evolution. At first, I wanted to do something molecular, to look for a cure for cancer. However, studying at the biology faculty is so arranged that you cannot just choose: here I want to do cancer research and nothing else.

At the biology faculty, the integral form of the biologist's thinking is very consistently built. We move from algae to vertebrates, then we consider all this in the context of evolution.

By the end of the fourth year, we have a picture of the world - and then you can do anything with it.

When I began to study science more professionally, I eventually went in the opposite direction: from a cure for cancer to evolution, animals and some kind of unity with nature. This gave me the realization that not everything that was interesting at first will certainly interest me all my life.

At one point, I had a scientific crisis. I studied cell biology - it seems so wonderful and interesting - but I no longer understood what I wanted in the end.

Then I realized that I had to look for something that could captivate me on the so-called spiritual level. I have written and read a lot outside of my field, covering topics from botany to neuroscience. It so happened that this direction became the most interesting for me.

I began to look for laboratories where my knowledge of molecular and cell biology would be useful. And at the same time, those where the work is associated with evolution and memory. So I ended up in the laboratory where I work now. For me, this was a conscious step away from mainstream science.

And then: who is not interested in what is going on in their heads?

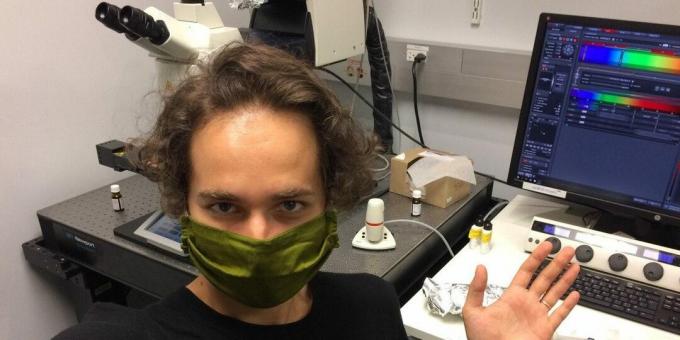

- You are studying the nervous system of slugs. Why slugs?

The advantage of aplysia (these are mollusks, which are also called sea hares) is in the simplicity of the nervous system and reflexes. With their help, you can study things that cannot be seen in most animals. Insert the electrodes where you will not work if you work with vertebrate cells. You can control the behavior of mollusks with the simplest manipulations - all the "tinsel" is removed, there are only the deepest connections of parts of the body.

What attracts me to aplysia is that most people, on the contrary, repulse it from it - how far in an evolutionary sense it is from humans.

Of course, it all depends on the task. If the goal of the work is close to a person - for example, to cure Alzheimer's disease, - then rodents are better suited here. We are very close in many ways. Mice are easy to modify: you can make them transgenic or artificially activate memory. However, it is worth noting that this does not work very effectively for humans: in mice, Alzheimer's disease has been cured a thousand times, but the results are not yet very easily transferred to humans.

If the task is to understand how the nervous system works, where it came from, what is its meaning, then this requires an organism that is remote from us. Comparing a person with him, you can see: this thing is specific to our body, but this is something fundamental, it has been sitting at the root of this nervous system for a billion years.

I am not interested in the physiology of aplysia, I am not interested in knowing how a snail feels. However, the simplicity of slugs allows me to study the nervous system as a whole, without the human being as an object.

- What is the most difficult part of the work of a neuroscientist?

Experiments. You need to get used to the idea that nothing works by default and can go on like this for years. There is a lot in neuroscience that you have to do with your hands and that takes months or years of training.

Any wrong move can ruin the whole experiment that you have been working on in recent months.

There is also an emotional component. It is very difficult to bang your head against the wall for a year and not go crazy. This has happened in my life more than once: you work on something for several years, and then it turns out that your work is not interesting to anyone, no one even wants to read it. Then you need to redo everything and do something that may not work at all for another year. It's emotionally difficult. On the other hand, it tempers, and, having received enough experience, you begin to take it a little more calmly. You just know in advance that a significant part of the incredible efforts will end up in the trash.

About evolution and memes

- How did the emergence of language / speech affect human evolution?

Everyone understands that language plays a fundamental role in the emergence of man. But there is a question over which many argue and to which there is no clear answer: what came first?

There are several possible options. Maybe language first appeared, and thanks to this we became so smart and civilized. Or maybe we have developed extraordinary abilities and, as a result, have created a language - a way of communication that depends on the presence of a very complex nervous system. These are two extreme options, but it seems to me that the truth is in the middle.

Without a very complex social brain, it is impossible to imagine the emergence of something like a language. But on the other hand, once it appears, language can influence genetic evolution. brain - and this has probably been the case for the last 200 thousand years.

I think the evolution of language, man and his brain in particular is a vicious circle, a self-fulfilling prophecy. The language becomes more complex - the brain becomes more complex, the language becomes more complex - and the brain accordingly.

This is similar to the co-evolution of flowering and insects. Obviously they evolved together. But who was the first? Are flowers matched to insects or insects to flowers? This is not so important. It is important that when they connect, they begin to evolve together. The same thing, in my opinion, happened with a person and his language.

- In your lectures, you talk about our ability to imitate different phenomena and people. What do you mean by that? What is the evolutionary significance of imitation for humanity?

When we hear the word "imitation," something bad comes to mind: that we are stealing, not producing our own. But any cultural phenomenon can be called imitation.

We get all ideas about reality from other people. We look at others to understand how to behave in society, how to go to work, how much rest, eat and sleep. This is imitation.

The ability to imitate is not unique to humans. Birds learn songs from their parents. Whales also learn to make their sounds from their surroundings. And in monkeys, imitation is what we call ape.

Imitation is precisely the seed that does not necessarily become culture, but gives us the opportunity to build culture and language.

I think the ability to imitate is related to the development of our brain, namely its ability to model and reflect the actions and thought processes of other people.

- We imitate many useless things. For example, taking drugs, playing on the phone or fashion. Does this mean that we went against evolution?

Question: the evolution of what? Drugs or games on the phone are precisely built into the human brain and provide exactly what that brain wants to do.

It usually seems to us that evolution is a single process: the origin of life, then monkey, then the cavemen, and now we are modern humans with computers and civilizations.

In fact, when in the evolutionary process we reach a person, a fundamentally new direction of evolution appears, which exists simultaneously with the ancient genetic evolutionary path. This is the evolution of culture. This is the transfer of knowledge, memes Hereinafter - a term introduced by Richard Dawkins, meaning a unit of information significant for culture. - Approx. ed. , ideas from person to person through the brain, and not through copying genes.

Memes and genes evolve in a very similar way. If we modernize the formulation of Charles Darwin a little, then we can say like this: units of information, genes and memes will move from the past to the future towards the greatest fitness.

But being fittest means different things to genes and to memes. For genes, this is a movement towards the most efficient organisms that have a high probability of passing genes from the previous generation to the next. Armor, teeth, longevity - all of these can help genes move from the past to the future.

And memes develop according to different laws. They do not move from body to body, but from brain to brain.

The only thing a meme strives for is to become more and more desirable for a person. It's getting better and better to fit into the demands of his brain.

So the meme movement doesn't have to be biologically beneficial to us.

- That is, as a selfish gene, only a selfish meme?

Absolutely right. This concept was just introduced by Richard Dawkins in the book "The Selfish Gene". In the same place, he compared the movement of a gene with the movement of another type of information, which he called a meme.

We can say that our ideas are the same selfishlike our genes. They don't care if they are helpful or not. They are only interested in how contagious they are. How attractive they are to people.

About memory and ways to improve it

Earlier in your research, you questioned the clear division of memory into short-term and long-term. How does memory work?

The separation of long-term and short-term memory is a matter of terminology. Different laboratories define these things in different ways: discretely or dividing into conventional categories.

The main idea of our laboratory, which we published several years ago, is that the expansion of the time boundary of memory is its fundamental mechanism. This is not the only transition from short-term to long-term, but a build-up of more and more lasting changes in the nervous system, which are memory.

All that our brain receives from the external environment is time intervals. On retina photons are falling, different air frequencies vibrate in the ears.

With what frequency and exactly which points appeared on the retina - this is the memory. Fundamentally, memory is fluctuations in homeostasis. When a signal arrives in our body, it vibrates some variable in the brain. Any signal is a wave. It's like a deviation, which then returns back to normal.

Let's say a few visual stimuli have caused a short-term abnormality in brain function. When faced with another short-term deviation - for example, from a sound stimulus - they together created a new, longer-term wave and became part of the memory.

Such transformations of short-term deviations into long-term ones occur at a huge number of levels. This is a pyramid that builds on itself.

From the point of view of the brain, there are no two types of memory: short-term and long-term. There are many abnormalities in the brain that, in certain combinations, lead to more and more lasting changes.

- Let's pretend I'm trying to learn a ticket for an exam. What is happening in my brain at this time?

The first thing that happens is that you direct your attention to this text, fix your eyes on the page. Visual information begins to flow through the retina into the thalamus, and from the thalamus into the visual cortex. That is, the signal from the retina is transmitted higher and higher to the brain.

When it reaches the cortex, it encounters a return signal that moves from the front of the brain, from the prefrontal cortex, where your motivation read the tutorial. You just won't explain to the monkey why you need to read this text. You have an idea why you are doing this and what you want to learn from it. This idea is projected from the prefrontal cortex into the visual cortex.

I'm oversimplifying a bit, but the point is that there is visual information coming through the eyes. And there is a top-down - attention, which illuminates this information and extracts from it elements that are important from the point of view of motivation. This second signal registers what you think is important and ignores what seems unimportant. Two signals interact with each other, synchronization is established between them.

This mental construction is translated into the hippocampus, an appendage of the cerebral cortex that is responsible for episodic memory. Episodic memory is a combination of different parts of the cortex that were active during a certain period of time. When something happens to you, your hearing, vision, smell are active - all this is connected by the hippocampus into an integral structure and is embedded in it by a single "hyperlink".

When you need to remember what you read in a textbook, the prefrontal cortex sends a request to the hippocampus. And he reproduces the state in which the prefrontal cortex was at the moment of memorization - during reading.

It turns out that memory consists of fixing synaptic connections and their relative strength in the hippocampus.

- What influences memorization to a greater extent? Motivation?

It is very difficult to separate motivation from attention. These are different names for a single process in the brain that is necessary for memorization.

Episodic memory really depends on motivation and, as a result, on attention, which is aimed at remembering. I somehow came up with the equation: memory = significance × repetition. This is a convention, but it reflects fundamental factors memorizing, which are as universal as possible and applicable to a large number of types of memory in different animals.

Significance can be physically expressed as a burst of neuromodulators - dopamine or norepinephrine - that are released by the brain when you are happy or scared. Relatively speaking, dopamine enters the hippocampus while synaptic contacts are being formed there, and enhances their formation. So if you're curious about what you're reading, if you're motivated, then hippocampal memorization will work better.

Repetition is also one of the fundamental properties of memory. If something is repeated at regular intervals, then it will have a greater effect. This is true even for creatures that do not have a nervous system. Bacteria can remember flashes of light at regular intervals and react to them as if they were forming a memory. There is something completely global in an evolutionary sense about repetition.

- You probably remember how in school days they learned poetry: in the evening we repeat many times, go to bed, in the morning we can recite a verse as a keepsake. How does sleep affect memory?

This is an absolutely logical technique. I have repeatedly found that teaching before bed is the most effective way to memorize. There are two factors at play here: repetition and the fact that it happens just before bedtime.

Neuroscientists agree that the fundamental function of sleep is closely related to memory. But how exactly is not yet very clear.

All living things have a slow sleep. REM sleep is a small superstructure on top of slow sleep, which is characteristic exclusively for us mammals. And maybe other vertebrates.

During REM sleep, we have dreams, and they seem to help us remember certain things. Sleep is an imitation of being awake. While the muscles of the body are disabled, the brain takes different pieces of memory and combines with each other. He looks at what happened, and if suddenly something useful has grown together, then this can be remembered.

Slow sleep, apparently, is needed for forgetting. During wakefulness, some of the synapses in the brain are strengthened, some are weakened, but strengthening prevails over weakening. By working the brain, we push it towards more and more strength of synapses. It cannot continue this way indefinitely, this state must be compensated. REM sleep is supposed to be a return to balance.

Sleep is a universal phenomenon in the animal kingdom, which in itself is paradoxical, because it is very dangerous: we are disconnected from the world for a significant period of time and are completely defenseless in front of predators. If sleep could be avoided, then evolutionarily we would definitely do it. It turns out that we definitely need sleep.

- Why do we remember the words of a stupid song that we heard a hundred years ago, and forget about the birthday of our best friend? How it works?

It is clear that a friend's birthday is more important to us than a song that we once heard. But this does not mean at all that our brain thinks the same way. For him - one more friend, one less, it is not so important. But the hit heard in the fifth grade is very important.

Of course, we would be happy to memorize socially important things and not memorize useless ones. But we don't always have control over what emotions different stimuli trigger in us.

It may also be that the songs and advertising are aimed at better memorization, to evoke an emotional reaction in us. Well, birthday is just a fact that in itself does not carry an emotional tint. All dates are the same, we ourselves need to create significance around a particular number in order to better remember it.

I have a feeling that 30% of my brain is devoted to advertising from the 90s. I am very worried about this. I can reproduce the ad for Malabar gum in great detail, but birthdays are much more difficult to remember.

- Isn't it evolutionarily more important to remember socially significant things, such as dates?

I totally agree that important things are evolutionarily more important to remember. It's just that this importance can be determined by different parts of the brain. I think the point is that we did not evolve with birthdays. Calendar and dates to remember are a recent cultural superstructure over the hard-coded processes in our brains. But the reaction to sounds is really something that is firmly in us.

- Can you improve your memory?

Attention is essential for memorization, and it can definitely be trained. And along with it, and memory. In addition, memory is easier to form not from scratch, but by adding elements to the already existing memory.

The more we know, the easier it is to remember.

Be interested in a large number of things, fill your memory - this will help you remember in the future.

About science, modern education and the book

- You worked as a scientist in the USA, Great Britain and Russia. How is Western science fundamentally different from Russian?

I hardly worked as a scientist in Russia. Studied, but this is not really work in the laboratory, and it was quite a long time ago. I have not lived in Russia for 12 years and I think that a lot has changed.

Feels like the main thing that distinguishes me and my classmates from the biology faculty from Western colleagues is the fact that we were taught to understand nature, and not to work as biologists. This has both pros and cons.

At the biology faculty we were brought up in such a way that to worry about practical things, to do science in order to create or cure something disease - this is unworthy of a real scientist. We do science like music. We create knowledge in a vacuum, we understand nature as it is, we live in the crystal castle of natural philosophy.

There is nothing like that in the West. Here this is a completely unthinkable position. If you are studying biology, then exactly how to be a biologist: how to work at a machine tool, run gels "Chasing gels" is a biologists' slang term for "separating and analyzing molecules by gel electrophoresis." - Approx. ed. and analyze the results. Here, no one cares what your ideas about nature and how botany and zoology fit into a single picture for you.

I don't know of a single Western neuroscientist who could draw a tree of life. But how can you study the brain without knowing what inhabits the planet? It seems like a very strange approach to me, with less intellectual work. And it was she who always attracted me in science.

Over the years of work in the laboratory, I realized that for productive scientific activity, once every six months I need to lift my head from the machine and think about what I am doing. If I orient myself in this way, then for the next six months I can forget about everything and conduct experiments monotonously.

I am very grateful that St. Petersburg State University gave me such an education, which allows you to look at everything from a bird's eye view, change the area of activity, if I want to.

- Is this attitude towards science what the United States lacks?

This is what I am missing. As practice shows, it is not at all necessary to make revolutions in understanding reality in order to be a successful scientist. I'm just interested in upheavals in understanding reality. And the practical aspects of the biologist's work are not interesting.

- Is there anything else that you are missing?

I am very critical of the publishing system in modern scientific publications. It is not related to work in the US or elsewhere. It's just that the reality is that scientific thought is guided by the priorities of the three commercial journals that decide where the world's science is headed. These are Cell, Nature and Science.

In China, for example, this was a particularly serious problem. Their government policy has broughtThe Truth about China’s Cash ‑ for ‑ Publication Policy the situation is absurd: a professor who sits on bread and water can submit one article to Nature and receive $ 20,000 as a prize. Such motivation to publish in these journals loses any scientific thought. This is exclusively a work for the magazine. And for many, there is a temptation to falsify data or present it in bad faith.

The process of submitting articles to these journals is also far from ideal. The problems of scientific peer review are being actively discussed now, because due to the coronavirus, they came to the surface. We saw how much slag can even get into a respected scientific publication.

The opposite situation is that what could have been published in those journals does not work simply because the reviewer's leg hurts today.

- How do you feel about modern education? What problems do you see and what would you improve?

Difficult question. Regarding education, I also have criticism, but, unfortunately, there are no special ideas on how to fix everything.

I have a feeling that the more widespread education becomes, the more honest it is, the more routine it is and the more it is based on cramming. Education in the past was a private interaction between student and teacher that takes into account the personality of the student. It is simply impossible to implement this on a scale of millions.

A mass education that gives everyone the same opportunity can only be organized with standardized tests. But standardization leads to the fact that we stop seeing the global picture and start working on these tests. Just as some scientists work exclusively for publication in Nature.

It may bear fruit, but personally I think there is something missing. Education should include a component that is not limited to testing knowledge. This can manifest itself through oral or at least written interaction, where a person has the opportunity to formulate his thoughts, ponder, apply them in life.

I give lectures twice a week to three sections, and in each section there are from 20 to 25 people, so I can well know all the students by name. I know who will be interested in what, from whom what to expect and who to push where. I wish there was more of this in education in general.

- Your book was recently published “Clap with one palm. How inanimate nature gave birth to the human mind». Can you tell us what the book is about?

The book is not about science, but about nature. I mention Darwin, Chomsky, Dobrzhansky, but they are not the main characters. The main characters are jellyfish, dinosaurs, archaea and ferns.

I wanted to describe the history of a person from the very beginning. Usually, when they say "human evolution", they mean the origin of man from ape. But this is the last moment in evolutionary history.

I refer to the book by Yuval Noah Harari “Sapiens. A Brief History of Humanity ". A wonderful book, I love it very much, but it starts with the chapter "Unremarkable animal". The idea is that before language we didn’t stand out, and then we invented it and everything became wonderful.

We can say that my book is a prequel or an expanded version of Sapiens, where I say that we were special long before the descent from the ape, at every turn of our evolutionary destiny. I wanted to trace this path from the very beginning: from inanimate matter to the moment when we became people who can speak, think in a human way, and solve human problems.

If the book says about the epithelium and ATP, then it automatically turns into "scientific", and if there are also jokes, then it also becomes "pop". Accordingly, the author turns into a popularizer of science, brings the light of scientific knowledge to the people. I have absolutely no such task. It's just that during my work in science, I learned quite a few different things. And every time I got to them, I invariably had the feeling “why didn't anyone tell me this before?” If someone had given me such a book when I was just starting to study biology, I would have died of happiness.

- Can you give your favorite moments from the book?

Why does a fish die when taken out of water? I had never thought about it before.

You can start with how the lungs differ from the gills. The lungs are a bag inside the body, and the gills are the same bag turned inside out and sticking out from the outside. So why do fish die in air? Seemingly, oxygen much more on land than in water.

It turns out that fish gills are so thin and soft that if you pull the fish out of the water, they stick together and the oxygen absorption surface decreases sharply. If you spread the gills, then the fish could well live in the air.

There is an organism that has terrestrial gills - this is the palm thief, or coconut crab. Its gills are saturated with chitin, so they are tough and help the coconut crab breathe calmly on land. But sea cucumbers can breathe their lungs underwater.

No one has ever explained to me the logic of the origin of photosynthesis.

It seems to me that this is the most important event that has happened in nature during the entire existence of life.

This is a fascinating story that at first photosynthesis took place on hydrogen sulfide. Then I switched from hydrogen sulfide to water: it has a very similar molecule, which is much more difficult to break down. When bacteria learned to break down water molecules, they ceased to depend on hydrogen sulfide sources.

The bottom line is that switching from this alternative substance to water means that photosynthesizing can be done anywhere. Photosynthesis became so efficient and simple that it spread massively around the world and began to produce oxygen as a by-product.

We are accustomed to seeing oxygen as something very useful. In fact it is poison: oxygen destroys everything it interacts with. The world was filled with this poison, as a result, most of the living organisms died at that time. This phenomenon is called oxygen holocaust. At the same time, it gave impetus to the emergence of eukaryotes, to more efficient fuel combustion and energy recovery from nutrients. Without all this, animals and humans would never have appeared.

It is simply impossible to imagine life on Earth in its current form without photosynthesis. I wanted someone to explain this to me at school or institute.

- What can you advise the readers of Lifehacker? Or maybe give some kind of parting words?

Buy my book, it will be good for your brain! I am not yet mature enough to give parting words. Just relax and everything will be fine.

Life hacking from Nikolai Kukushkin

Hobbies and recreation

My favorite form of recreation is going out into nature. Nowhere do I feel so free and good as in the forest, mountains or at sea. This is always the most pleasant and valuable for me, which helps to accumulate material for lectures, books and everything else. I watch nature live, I come into contact with it.

I also really love prepareand I have a scientific approach to culinary arts. I am interested in understanding how foods are chemically modified and how this can be done more efficiently.

All my life I am also fond of music, this is a very important element of my life. Once I dabbled in the guitar, even played in a group in my student years, but all this is the case of bygone days.

Books

I hardly read fiction. An exception - "War and Peace"Leo Tolstoy, this is my favorite book. I reread it a couple of years ago when I started writing mine.

I am very interested in historical literature. For example, "Silk road»Peter Frankopan - about world history from the perspective of Central Asia, Persia and the Middle East. I recently read William Dalrymple's book Anarchy, which talks about the British East India Company. I also advise “Shotguns, germs and steel"Jared Diamond. This is an impressive work that made a very strong impression on me and influenced my understanding of world history and biology. I'm currently reading a book by Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, about how we are being followed by Google and Facebook.

From scientific pop I advise “Sapiens. A Brief History of Humanity"Yuvala Noah Harari and"Selfish gene"Richard Dawkins is a classic that anyone interested in biology should know. My idol in the philosophy of mind, evolution and neuroscience is Daniel Dennett, I recommend all his books.

Films and series

I don't watch anything related to Disney or superheroes. I have nothing against the latter, but in recent years I have repeatedly tried to get interested in them, but in the end nothing came of it.

One of the best I've watched in years is Phoebe Waller-Bridge's Fleabag (Shit). I also recommend the first season of Killing Eve. In general, I like what it does HBO. I'm a huge Game of Thrones fan. I also recommend the Succession series, The Last Dance about Michael Jordan, and the Getaway Comedy about a marijuana dealer who delivers his product around New York City.

Music

For the last ten years I have been listening mainly to house, techno and jazz. My favorite labels are Rhythm Section International, Banoffee Pies, Dirt Crew, Lagaffe Tales, Idle Hands. London is a great time for jazz, for example the Giles Peterson show on BBC6. There are still a lot of interesting things in South America: Chancha Via Circuito, Nicola Cruz, Nicholas Jar - my last idol.

My running playlist is mostly down-to-earth post-punk like the Gang of Four and The B-52s. And also “Mummy Troll"And" Cartoons "because there is nothing better for running than what you listened to in 6th grade.

If I had to choose one of my favorites, I think I would choose Romanian minimal techno. Listen, for example, to Petre Inspirescu or Rhadoo, in general, the entire catalog of the legendary arpiar label. Like the guitar, I once dabbled in DJing and producing a little bit, but now I prefer to listen to those who do it better than me.

Podcasts

I love 99% Invisible, a podcast about design and architecture. And The Anthropocene Reviewed, where different aspects of our planet are reviewed on a five-star scale.

Read also🧐

- Jobs: Alexander Panchin, biologist and popularizer of science

- "The challenge of modern medicine is to help you live to see your Alzheimer's." Interview with cardiologist Alexey Utin

- Jobs: Alexey Vodovozov - science popularizer, journalist and medical blogger