Why is the rumor that a new coronavirus was bred in a lab wrong?

Health / / December 28, 2020

Popular science edition about what's happening in science, engineering and technology right now.

Research on deadly viruses often seems too risky to people and serves as a source for the emergence of conspiracy theories. In this sense, the outbreak of the COVID-2019 pandemic was no exception - panic rumors constantly appear on the Web. that the coronavirus that caused it was grown artificially and either on purpose, or through an oversight, released in shine. In our material, we analyze why people continue to work with dangerous viruses, how this happens and why the SARS ‑ CoV ‑ 2 virus does not at all look like a fugitive from the laboratory.

Human consciousness cannot accept disaster as an accident. Whatever happens - a drought, a forest fire, even a meteorite fall - we need to find some reason for what happened, something that will help answer the question: why did it happen now, why did it happen to us and what needs to be done to prevent it from happening again?

Epidemics are no exception here, rather, even the rule is not to count conspiracy theories around

HIVFolklorists' archives are bursting with stories of contaminated needles left behind in movie theater seats, infected pies."Biological Chernobyl"

The current epidemic, which has entered literally every home, also requires a rational - that is, magical - explanation. Many people needed to find an understandable and, preferably, removable cause, and it was found almost immediately: this "biological Chernobyl" was provoked by scientists and their irresponsible experiments with viruses.

I must say that once "biological Chernobyl" really happened, however, it did not look like the current coronavirus pandemic. This happened at the very beginning of April 1979 in Sverdlovsk (today's Yekaterinburg), where people suddenly began to die quickly from an unknown disease.

The disease turned out to be anthrax, and its source was a plant for the production of bacteriological weapons, where, according to one version, they forgot to replace the protective filter. A total of 68 people died, with 66 of them, as the authors of the study publishedThe Sverdlovsk anthrax outbreak of 1979 in the journal Science in 1994, lived exactly in the direction of the emission from the territory of the military camp 19.

This fact, as well as an unusual form of the disease for anthrax - pulmonary - leaves little room for the official version that the epidemic was associated with contaminated meat.

“The affected city faced not some kind of plague hybrid, not mixed, but anthrax from a special strain - with a stick with a perforated shell from another, streptomycin-resistant strain B 29 ", - wroteDeath from a test tube. What happened in Sverdlovsk in April 1979? one of the researchers of the history of this accident, Sergei Parfyonov.

The victims of this accident died from specially developed "military" pathogens designed for the rapid and mass murder of people.

Can we say that something similar is happening now, but on a global scale? Could scientists have created a new, more dangerous artificial virus? If so, how and why did they do it? Can we identify the origin of the new coronavirus? Can we assume that thousands of people have died because of biologists' mistake or crime? Let's try to figure it out.

Birds, ferrets and the moratorium

In 2011, two research teams led by Ron Fouche and Yoshihiro Kawaoka said they had managed to modify the H5N1 avian influenza virus. If the original strain can be transmitted to a mammal only from a bird, then the modified one could also be transmitted among mammals, namely ferrets. These animals were chosen as model organisms because their response to the influenza virus is closest to that of humans.

Articles describing the results of the research and describing the methods of work were sent to the journals Science and Nature - but were not published. The publication was stopped at the request of the US National Science Commission on Biosafety, which considered that the technology for modifying the virus could fall into the hands of terrorists.

The idea of making it easier for a dangerous virus that kills 60 percent of diseased birds to spread to mammals has sparked heated debateBenefits and Risks of Influenza Research: Lessons Learned and in the scientific community.

The fact is that it is much easier for a virus that has learned to spread in ferrets to learn to spread in humans if it "escapes" from the laboratory.

The result of the discussion was a voluntary 60-month moratorium on research on this topic, canceled in 2013 after the adoption of new regulations.

The works of Fouche and Kawaoka were eventually publishedAirborne Transmission of Influenza A / H5N1 Virus Between Ferrets (although some key details were removed from the articles), and they clearly demonstrated that for the transition the virus needs very little to spread between mammals and the risk of such a strain in nature great.

In 2014, after several incidents in American laboratories, the US Department of Health completely stopped projects related to research on three dangerous pathogens: the H5N1 influenza virus, MERS and SARS. Nevertheless, in 2019, scientists managed to agreeEXCLUSIVE: Controversial experiments that could make bird flu more risky poised to resume that part of the work on the study of bird flu will nevertheless continue with enhanced safety measures.

Such precautions are not unfounded - there are cases when viruses "escaped" from civilian laboratories. So, a few months after the end of the SARS ‑ CoV epidemic in 2003, they fell ill with pneumoniaSARS Update — May 19, 2004 two students from the National Institute of Virology in Beijing and seven others associated with them. The institute's SARS laboratory was immediately closed, and all victims were isolated, so that the disease did not spread further.

Disaster in vitro

Why would ordinary civilian scientists, not military and not terrorists, risk the lives of millions of people by creating potentially dangerous strains of viruses? Why can't we limit ourselves to studying already existing viruses, which also cause a lot of problems?

In short, scientists want to master the method of predicting exactly how a disaster can occur, and in advance to find a way to stop it, or at least reduce the damage.

The emergence of a deadly and easily spreading virus with unexplored behavior poses a threat to humans. If scientists and doctors understand exactly how the transformation of a potential pathogen occurs and in advance know its basic properties, to resist a new misfortune - or to prevent it - becomes significantly easier.

Many major epidemics in recent years have been associated with the fact that a virus spread among animals, as a result of evolution, acquired the ability to infect people and be transmitted from person to person.

Previous epidemics of avian influenza and SARS and MERS syndromes were triggered by human contact with animals - hosts of viruses: birds, civets, one-humped camels. Despite the fact that the epidemic was stopped and the virus disappeared from the human population, it always remained in the natural reservoir and at any moment could again "jump" onto a person.

Scientists have demonstratedTransmission and evolution of the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in Saudi Arabia: a descriptive genomic studythat the virus that provokes MERS "jumped" from its main host - a one-humped camel - to more than one person times, so that each outbreak of the disease was associated with a separate transition and provoked by independent mutations virus.

Since the 2003 SARS ‑ CoV SARS epidemic, many articles have been published (e.g. time, two and three), the main message of which was that in nature there is a constant "reservoir" of viruses similar to SARS ‑ CoV. Their hosts are mainly bats, and the likelihood of the virus "jumping" from them to humans is high, so you should be prepared for a new epidemic, it was saidSevere Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus as an Agent of Emerging and Reemerging Infection in a review published back in 2007.

In this transition, intermediate hosts play an important role, in which the virus can undergo the necessary adaptation. In the case of the 2003 epidemic, civets played this role. At first, the bat virus lived in them without causing symptoms, and only then - after adapting - jumped to humans.

This was not the only potentially dangerous strain: in 2007, in the vicinity of the same Wuhan, researchers discoveredNatural Mutations in the Receptor Binding Domain of Spike Glycoprotein Determine the Reactivity of Cross-Neutralization between Palm Civet Coronavirus and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus civets - carriers of a virus sister to the SARS ‑ CoV strain, which is very poor for testing, but could bind to receptors on human cells.

In 2013, horseshoe bats were found inIsolation and characterization of a bat SARS ‑ like coronavirus that uses the ACE2 receptor a coronavirus capable of using not only their own ACE2 receptors, but also civet and human receptors to enter cells. This called into question the need for an intermediate host.

Later in 2018, researchers from the Wuhan Institute of Virology showedSerological Evidence of Bat SARS ‑ Related Coronavirus Infection in Humans, Chinathat the immune systems of some people living near caves where bats live are already familiar with SARS-like viruses. The percentage of such people turned out to be small, but this clearly indicates: viruses regularly "check" the ability to settle in a person, and sometimes they succeed.

To predict the threat posed by a potential pathogen, you need to understand exactly how it can change and what changes are enough for it to become dangerous. Often for this, mathematical models or studies of an already past epidemic are not enough; experiments are necessary.

Coronavirus-chimera

It was in order to understand how dangerous the viruses circulating in the population of bats are, in 2015, with the participation of the same laboratory in Wuhan,A SARS ‑ like cluster of circulating bat coronaviruses shows potential for human emergence a chimera virus, assembled from parts of two viruses: the laboratory analogue of SARS ‑ CoV and the SL ‑ SHC014 virus, common in horseshoe bats.

The SARS ‑ CoV virus also came to us from bats, but with an intermediate "transplant" in a civet. The researchers wanted to know how much a transplant was needed and to determine the pathogenic potential of SARS ‑ CoV's bat relatives.

The most important role in whether a virus can infect a particular host is played by the S-protein, which gets its name from the English word spike ("thorn"). This protein is the main instrument of viral aggression, it clings to the ACE2 receptors on the surface of the host cells and allows penetration into the cell.

The sequences of these proteins in different coronaviruses are quite diverse and are "adjusted" in the course of evolution for contact with the receptors of their particular host.

Thus, the sequences of S ‑ proteins in SARS ‑ CoV and SL ‑ SHC014 differ in key places, so the researchers wanted to find out if this prevents the SL ‑ SHC014 virus from spreading to humans. Scientists took the S ‑ protein SL ‑ SHC014 and inserted it into a model virus used to study SARS ‑ CoV in the laboratory.

It turned out that the new synthetic virus is not inferior to the original one. He could infect laboratory mice, and at the same time penetrate the cells of human cell lines.

This means that viruses inhabiting bats already carry “details” that can help them spread to humans.

In addition, the researchers tested whether vaccination of laboratory mice with SARS ‑ CoV can protect them from the hybrid virus. It turned out that no, so even people who have had SARS ‑ CoV may be defenseless against a potential epidemic and old vaccines won't help.

Therefore, in their conclusions, the authors of the article emphasized the need to develop new drugs, and later adoptedBroad ‑ spectrum antiviral GS ‑ 5734 inhibits both epidemic and zoonotic coronaviruses direct participation in this.

A similar inverse experiment - the transplantation of a region of the S ‑ protein SARS ‑ CoV to the bat virus Bat ‑ SCoV - was carried outSynthetic recombinant bat SARS-like coronavirus is infectious in cultured cells and in mice even earlier, in 2008. In this case, synthetic viruses were also able to multiply in human cell lines.

Here he is?

If scientists can create new viruses, including those potentially dangerous to humans, moreover, if they have already experimented with coronavirus and created new strains, then does this mean that the strain that caused the current pandemic was also made artificially?

Could SARS ‑ CoV ‑ 2 have simply "escaped" the laboratory? It is known that this "escape" led to a small outbreakChina's latest SARS outbreak has been contained, but biosafety concerns remain - Update 7 SARS in 2003, after the end of the "main" epidemic. To answer this question, you need to understand the details of the technology and understand exactly how the modified viruses are made.

The main method is assembling one virus from parts of several others. This method was just used by the group of Ralph Baric and ZhengLi-Li Shi, who created the chimera described above from the “details” of the SARS ‑ CoV and SL ‑ SHC01 viruses.

If the genome of such a virus is sequenced, then you can see the blocks from which it was built - they will be similar to the regions of the original viruses.

The second option is to reproduce evolution in a test tube. Avian influenza researchers followed this path, selecting viruses that were more adapted to reproduce in ferrets. Despite the fact that such a variant of obtaining new viruses is possible, the final strain will remain close to the original one.

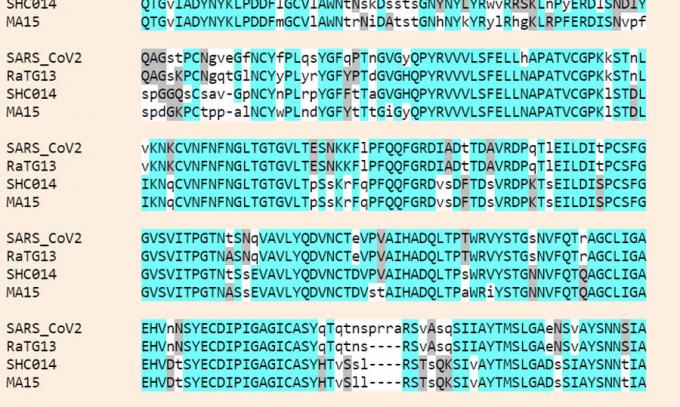

Who caused today's pandemic the strain does not fit any of the listed options. First, the SARS ‑ CoV ‑ 2 genome does not have such a block structure: the differences from other known strains are scattered throughout the genome. This is one of the signs of natural evolution.

Secondly, no insertions similar to other pathogenic viruses have been found in this genome either.

Although a preprint was published in February, the authors of which allegedly found HIV insertions in the genome of the virus, upon closer examination it turned outHIV ‑ 1 did not contribute to the 2019 ‑ nCoV genomethat the analysis was carried out incorrectly: these areas are so small and not specific that they can just as well belong to a huge number of organisms. In addition, these regions can also be found in the genomes of wild bat coronaviruses. As a result, the preprint was withdrawn.

If we compare the genome of the chimera coronavirus synthesized in 2015, or two original viruses for it with the genome of the pandemic strain SARS ‑ CoV ‑ 2, then it turns out that they differ by more than five thousand letter-nucleotides - this is about one-sixth of the total length of the virus genome, and this is a very large discrepancy.

Therefore, there is no reason to believe that the modern SARS ‑ CoV ‑ 2 is the 2015 version of the synthetic virus.

Wild relatives

A comparison of the genomes of coronaviruses showed that the closest known relative of SARS ‑ CoV ‑ 2 is RaTG13 coronavirus found in the Yunnan horseshoe bat Rhinolophus affinis in 2013 year. They share 96 percent of the genome.

This is more than the others, but, nevertheless, RaTG13 cannot be called a very close relative of SARS ‑ CoV ‑ 2 and that one strain was turned into another in the laboratory.

If we compare SARS ‑ CoV, which caused the 2003 epidemic, and its immediate ancestor, a civet virus, it turns out that their genomes differ by only 202 nucleotides (0.02 percent). Difference between "wild" and laboratory-derived virus strain flu less than a dozen mutations.

Against this background, the distance between SARS ‑ CoV ‑ 2 and RaTG13 is huge - more than 1,100 mutations scattered throughout the genome (3.8 percent).

It can be assumed that the virus evolved for a very long time inside the laboratory and acquired so many mutations over many years. In this case, it will indeed be impossible to distinguish a laboratory virus from a wild one, since they evolved according to the same laws.

But the likelihood of the appearance of such a virus is extremely small.

During storage, viruses are tried to be kept at rest - precisely so that they remain in their original form, and the results of experiments on them are recorded in the regularly appearing publications of the Wuhan Shi Laboratory Zhengli.

It is much more likely to find the direct ancestor of this virus not in the laboratory, but among the coronaviruses of bats and potential intermediate hosts. As already mentioned, civets have already been found in the Wuhan region - carriers of potentially dangerous viruses, there are other possible vectors. Their viruses are diverse, but poorly represented in databases.

By learning more about them, we will most likely be able to better understand how the virus got to us. Based on the genealogical tree of genomes, all known SARS-CoV-2 are descendants of the same virus that lived around November 2019. But where exactly his close ancestors lived before the first cases of COVID-19, we do not know.

Two special areas

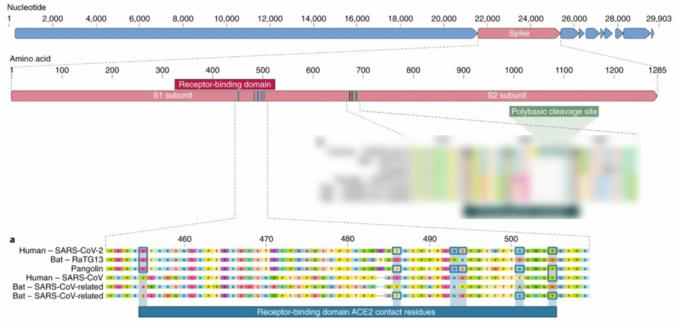

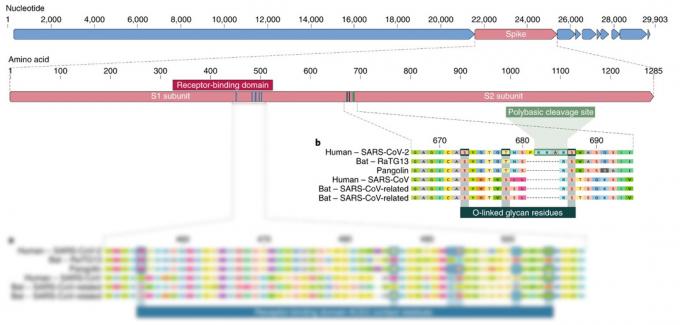

Despite the fact that differences from other known coronaviruses are scattered throughout the genome SARS ‑ CoV ‑ 2, the researchers concluded that mutations key for human infection are concentrated in two regions of the gene encoding the S-protein. These two sites are also of natural origin.

The first one is responsible for proper binding to the ACE2 receptor. Of the six key amino acids in this region, related viral strains have no more than half the same, and the closest relative, RaTG13, has only one. The pathogenicity for humans of a strain with such a combination has been described for the first time, and an identical combination has so far been found only in the sequence of the pangolin coronavirus.

From the fact that these key amino acids are the same in pangolin virus and in humans, it cannot be concluded that this region has a common origin. This can be an example of parallel evolution, when viruses or other organisms independently acquire similar features.

The most famous example of such a process is when bacteria independently of each other acquire resistance to the same antibiotic. Likewise, a virus, adapting to life in organisms with similar ACE2 receptors, can evolve in a similar way.

An alternative scenario for obtaining such a picture, on the contrary, assumesPangolin homology associated with 2019 ‑ nCoVthat all six key amino acids were present in the common ancestor of the pangolin virus, RaTG13 and SARS ‑ CoV ‑ 2, but were later replaced in RaTG13 by others.

In addition to human cells, the S ‑ protein SARS ‑ CoV ‑ 2 is possibly capable ofReceptor Recognition by the Novel Coronavirus from Wuhan: an Analysis Based on Decade ‑ Long Structural Studies of SARS Coronavirus recognize the ACE2 receptors of other animals, such as ferrets, cats or some monkeys, due to the fact that the molecules of these receptors are identical or very similar to humans in the places of their interaction with virus. This means that the range of hosts of the virus is not necessarily limited to humans, and for a long time he could “train” interaction with similar receptors while living in another animal. (This is a theoretical assumption based on calculations - there is no evidence that the virus could be transmitted through domestic animals such as cats and dogs.)

Could these amino acids have been inserted artificially?

It is known from previous research that S ‑ protein is highly variable. This variant of six amino acids is not the only one capable of teaching the virus to cling to human cells and, moreover, as shownReceptor Recognition by the Novel Coronavirus from Wuhan: an Analysis Based on Decade ‑ Long Structural Studies of SARS Coronavirus in one of the recent works, not ideal from the point of view of the "harmfulness" of the virus.

As described above, the sequences of S ‑ proteins capable of binding to ACE2 receptors have been known for a long time, and artificial "Improving" the virus with the help of this previously unknown amino acid sequence - moreover, not optimal - it seems unlikely.

The second feature of SARS ‑ CoV ‑ 2 S ‑ protein (apart from those six amino acids) is the way it is cut. In order for the virus to enter the cell, the S ‑ protein must be cut at a certain place by the enzymes of the cell. All other relatives, including viruses bats, pangolins and humans, the cut is only one amino acid, while SARS ‑ CoV ‑ 2 has four.

How this additive affected its ability to spread to humans and other species is not yet clear. It is known that a similar natural transformation of the incision site in avian influenza significantly expandedThe proximal origin of SARS ‑ CoV ‑ 2 the circle of its owners. However, there are no studies to confirm that this is true for SARS ‑ CoV ‑ 2.

Thus, there is no reason to believe that the SARS ‑ CoV ‑ 2 virus is of artificial origin. We do not know of his close enough and at the same time well-studied relatives who could serve as a basis for synthesis, scientists also do not have any insertions into its genome from previously studied pathogens discovered. However, its genome is organized in a manner consistent with our understanding of the natural evolution of these viruses.

You can think of a cumbersome system of conditions under which this virus could still escape from scientists, but the prerequisites for this are minimal. At the same time, the chances of a new dangerous strain of coronavirus emerging from natural sources in the scientific literature of the last decade have been regularly assessed as very high. And SARS ‑ CoV ‑ 2, which caused the pandemic, is exactly in line with these predictions.

Read also😷

- How to treat coronavirus

- How to survive a pandemic

- 7 ways to tame coronavirus anxiety